This is my attempt to make the HTTPbis caching rules more accessible and hopefully shine a light on how powerful HTTP caching can be.

I’ve been working on a Pluralsight course that talks about how to use the Microsoft HttpClient library. One of the areas I cover is how to take advantage of HTTP caching. In the process I have been doing quite a bit of reading of the HTTPbis spec document on caching. It isn’t the easiest of specifications to read as there are many interdependencies between the directives and there are a many different scenarios that are supported.

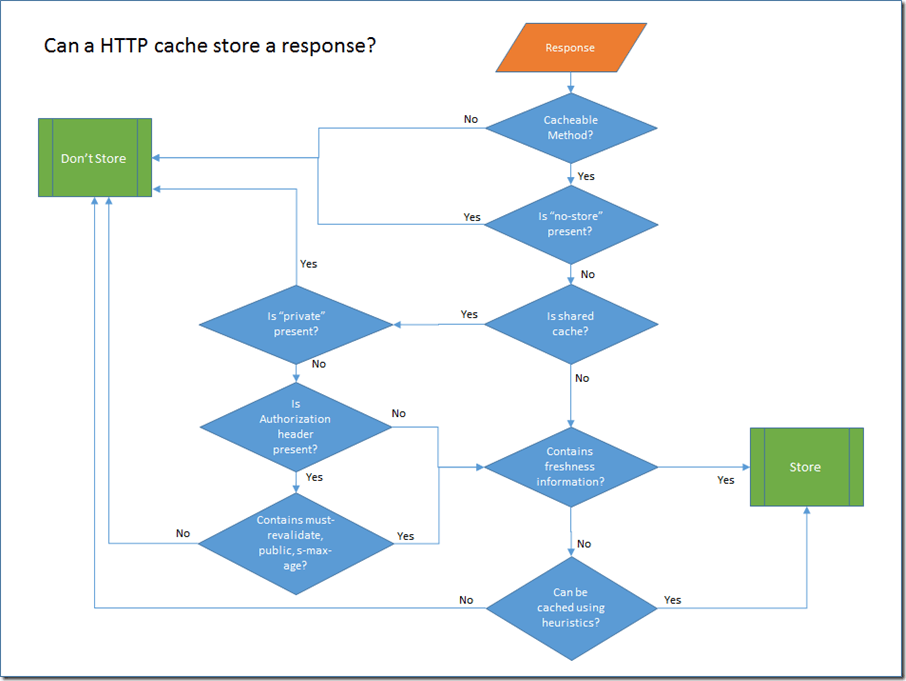

To help me get a grip, I decided I needed to draw some diagrams to help me get a clearer picture of the rules. The rules break down into two distinct steps:

- Is a cache allowed to store a response that is returned from an Origin Server?

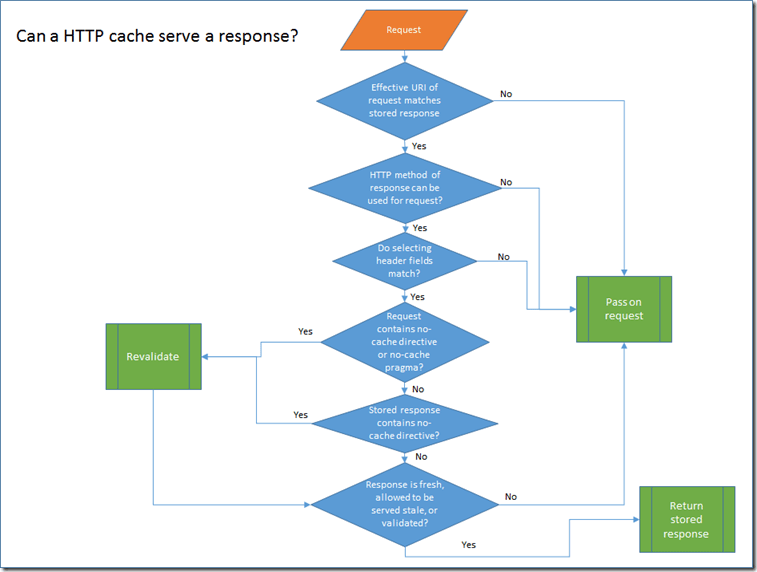

- Can a response be served from the cache for a particular request?

Cacheable Methods

GET and HEAD responses may be cacheable.

POST responses may be cacheable, but will only be served to a subsequent GET request. A POST request will never receive a cached response.

The response to PUT, DELETE, CONNECT, TRACE and OPTIONS are not cacheable.

Is No-store present?

In this test we much check both the response cache-control header that comes back from the server and the equivalent request header. If either contain the no-store directive then response should not be held onto for any longer than it takes to return it to the client.

Is shared cache?

HTTP Caches are classified into two distinct types, shared and private. A shared cache stores responses that are to be reused by more than one user. Shared caches are the ones you find sitting in front of web servers, or at the edge of corporate networks. Private caches are usually pieces of software that are either built into the client OS or the client application.

Probably the most important difference in the behaviour of private caches is that they are allowed to store responses that contain authentication headers. This behaviour which keeps your authentication credentials out of shared caches is probably one of the best arguments for using authorization header instead of some custom header or URI query parameter.

The presence of headers like must-revalidate, public and s-max-age override this limitation on shared caches not being able to store responses with an authorization header. I understand why using public and s-max-age might do that, but I’m puzzled as to why must-revalidate does.

Contains Freshness Information?

If a response contains freshness directives like max-age, Expires, or s-max-age, then we know that the server considers the response cacheable.

Can be cached using heuristics?

If no explicit freshness information is provided, then responses with the following status can still be cached using heuristic based caching: 200,203,204,206,300,301,404,405,410,414,501. The details of the heuristics algorithm are specific to the particular client application. For example Internet Explorer uses a fraction of the difference between the last modified date and the current time as the max-age. This is the suggested algorithm in RFC2616. If the last-modified header is not present, then it falls back to user defined settings for caching that response.

Once a response has been stored, then future requests may reuse that stored response.

Effective URI matches stored response?

The request URI is used as part of the primary cache lookup key. The other part is the request method which we will talk about next. The term “Effective URI” is used because on the server side some processing is needed to reconstruct the URI that the client used to make the request.

Can HTTP request method return cached responses?

The second part of the primary cache lookup key is the the HTTP method. As we mentioned earlier, only GET and HEAD requests can return cached responses. However, because the GET and HEAD request for the same resource return different representations they are treated as distinct cache entries. I wondered if it might be acceptable to generate the HEAD cached response directly from a stored GET response by simply stripping off the body. However, I’m not sure if that is allowed because you can use HEAD requests to freshen stored GET responses. Here is the relevant part of the spec, maybe someone else can do a better job of decoding it than me!

Do selecting header fields match?

This innocuous little question deserves a blog post all of it’s own so please accept that I am only skimming the surface here. This test is used when the stored response contains a vary header. When the header fields identified in the vary header contain matching values in both the new request and the stored response then the stored response can be used to satisfy the request.

Does request or response contain no-cache directive?

A request that contains a no-cache directive in either the cache-control header or the pragma header will not allow a stored response to be used directly even if it is fresh. Before it can be used, the cache must make a conditional request back to the server to confirm that the stored response is still valid. Once that is confirmed, then the stored response can be returned. So, to re-iterate, just because you sent a request with no-cache, doesn’t mean that you won’t get a response served from a cache. However, you will be guaranteed that it is up to date.

The same revalidation process occurs if the stored response contains a no-cache header. Most people are surprised when they find out that no-cache doesn’t mean “don’t cache”. It simply means “must-revalidate even if still fresh”.

You might notice that there is no check for the no-store request header in the diagram. The no-store request header is only tested when determining if a response can be cached. If some other user of a shared cache issues a request to a resource that is cacheable and then you issue a request to the same resource with no-store, you could still return a cached response.

So can we finally serve this response?

If the stored response is still fresh. I.e. the expired date has not passed, or the date retrieved plus max-age has not passed, then the response can be served. If the response is stale and the client sends a max-stale directive then it may also be possible to serve the stale response. And finally, if we have just finished re-validating the response, then we can return it.

That’s a high level overview of the process. There are lots of details I skipped, but that’s why the full caching specification is 40 pages! Hopefully, this overview will make it easier when you want to dig into more details in the spec.

Show me the code!

If you are interested to see what this process might look like in code, I have started building a private cache implementation here. Hopefully, I will get comments working again on this blog soon, but in the meanwhile, come find me on twitter with any questions you might have. @darrel_miller